Brutalism.

Derived from the French term of Béton Brut, or ‘raw concrete’, Brutalism is an architectural style popularised in the 1960s, characterised in many parts of the world by the use of exposed and unfinished concrete.

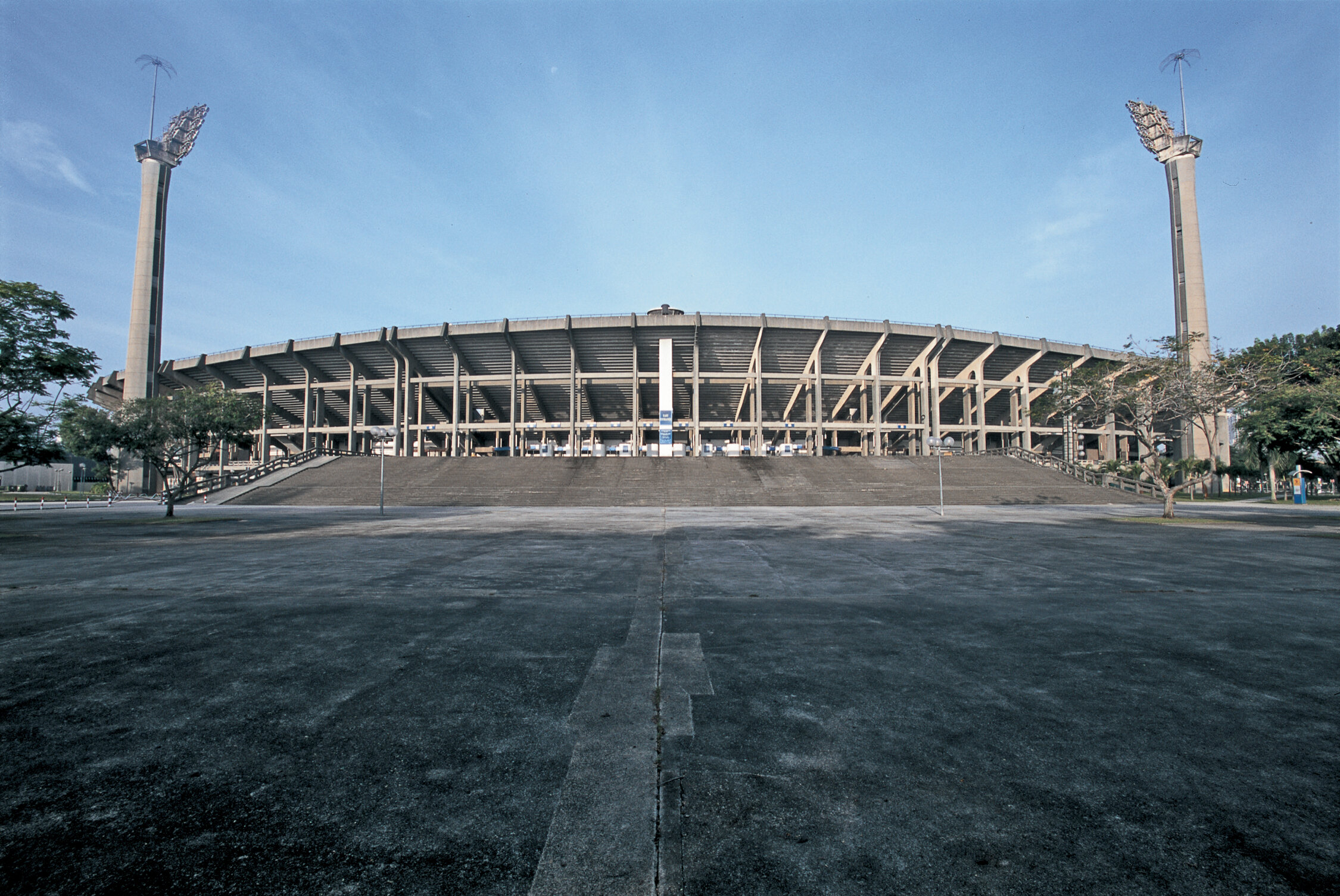

Katong Shopping Centre. Photo by Darren Soh.

With the articulation of its structural frame in an undisguised manner, Brutalist buildings tend to impose a sense of monumentality with its visual weight and massiveness. Guided by a functionalist ethos, clarity of structure and purity of material use is favoured over decorative design, promoting a correlation between form and function. The presence of recurring modular elements, distinct spatial zones, expression of building services, and projection of circulation cores, all unify at a monumental scale to celebrate modern construction and technology. Raw geometric forms form the basis of its architectural design language, with apertures treated as voids in solids, resulting in deep-shadowed façade punctuations.

As a philosophical approach, Brutalism strives to engender simple, honest, and functional buildings that accommodate their purpose and users. Although one of Brutalism’s main features was the use of exposed concrete, this was not the case for those built in Singapore. Their concrete surfaces were often plastered over and painted; and even finished with Shanghai Plaster. According to Singapore architect Tay Kheng Soon, “Brutalism, apparently, was too brutal for the bureaucrats.”¹ When the Buildings and Common Property (Maintenance and Management) Act was established in 1973 to ensure owners and developers maintained structures they have built and leased to the public, the Building Management Unit required that a building’s “more bluntly exposed concrete areas to be painted over”². After all, exposed concrete does not weather well in the equatorial climate of Singapore, and if not well-detailed and sealed, algae and mould would grow on its porous surface.

In Singapore, many different associations were formed with these plastered and painted over Brutalist buildings. In general, those owned by the state or its agencies were well-maintained and well-regarded. For example, the Jurong Town Hall (1974) and Singapore Science Centre (1977) were widely seen as futuristic and forward-looking, and the former Subordinate Courts (1975) and former PUB Building (1977) were generally deemed as appropriately monumental and institutional. Unfortunately, the strata-titled and poorly-maintained commercial examples of Brutalism tended to be perceived negatively by some members of the public due to their unkempt appearances and depreciating property values. There is nothing intrinsically brutal about Brutalism.

Subordinate Court. Photo by Darren Soh.

Amoy Street Market. Photo by Darren Soh.

Last updated 14 May 2021. Written by Jonathan Yee and Chang Jiat Hwee.

¹ Tay Kheng Soon, “Architects, Be Your Own Critics,” The Business Times, 6 September 1978.

² “Building Management Unit,” Singapore Institute of Architects’ Journal 64 (1974).

References:

Banham, Reyner. The New Brutalism (London: Architectural Press, 1966).

Heuvel, Dirk van den. ‘Between Brutalists. The Banham Hypotesis and the Smithson Way of Life’, The Journal of Architecture, 20(2): 293-308. Delft, Netherlands, 2015.

‘A Movement in a Moment: Brutalism’ in Phaidon, accessed 14 May 2021.