SG60: Restore the Dignity of SCHTUH to Celebrate Singapore’s Independence

A monument to Singapore’s labour movement

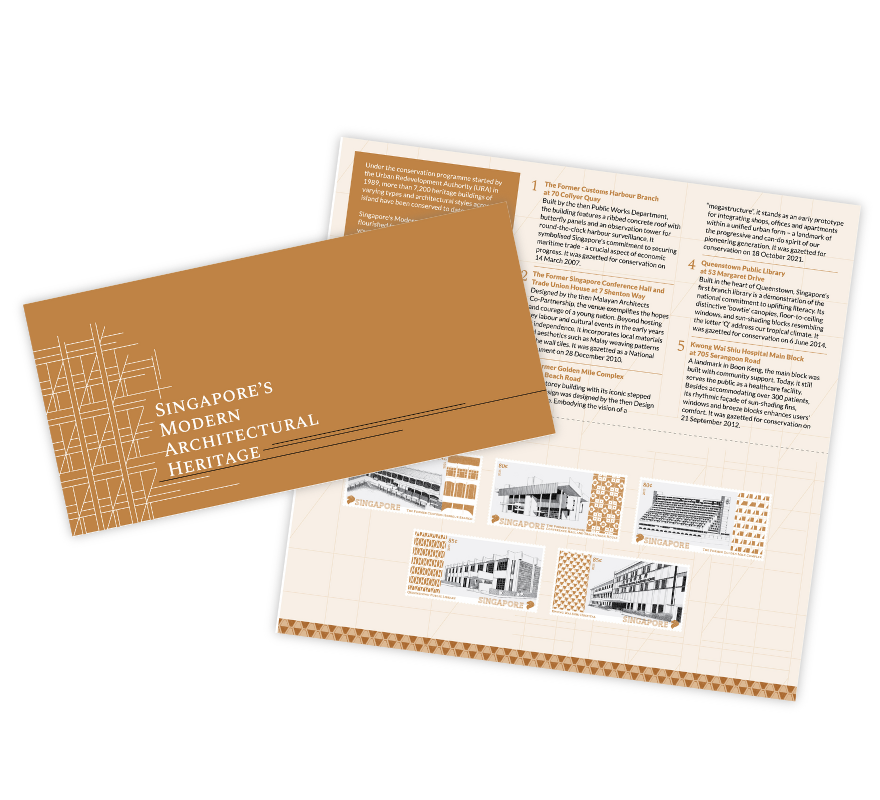

Did you know that the Singapore Conference Hall, a national monument, was previously known as the Singapore Conference Hall and Trade Union House (SCHTUH)? Although the headquarters of the labour movement has long since been relocated from the building at Shenton Way, it was a critical part of its heritage.

At the opening of the building in 1965, then Secretary-General of the National Trade Union Congress Devan Nair noted:

“The Government of Singapore today honours a tryst with the Labour Movement. In 1959, the election platform of the People's Action Party contained a promise to build a fitting headquarters for the Movement. It was a promise given by a political party which was singularly conscious of the key role of labour in the creation of a free, democratic and socialist society in Singapore… The tryst has been kept, the promise fulfilled. This magnificent Trade Union House and Conference Hall, without comparison in any other part of the developing world, will long remain a testimony and a symbol of the key role in Singapore of the democratic Labour Movement, and of its pride of place and influence in the affairs and councils of the Nation, and on Singapore's chosen road to a more just and equal socialist society.”

The Minister of Culture and Social Affairs at that time, Othman Wok, added:

“In an independent Singapore founded on the principles of liberty and justice and an ever seeking welfare and happiness of people in a more just and equal society, it follows that Trade Unions must have accommodation commensurate with the dignity of labour… This newly completed Singapore Conference Hall and Trade Union House will provide all trade unionists with ample facilities to enable them to lead fuller social lives… Much effort has gone into this project and now this building asserts itself as an index of the dignity of labour in Singapore.”

The first pile of the building was appropriately driven by a trade unionist, Mr. S. Munusamy, on August 8, 1962.

“Boy, this place has got it!”

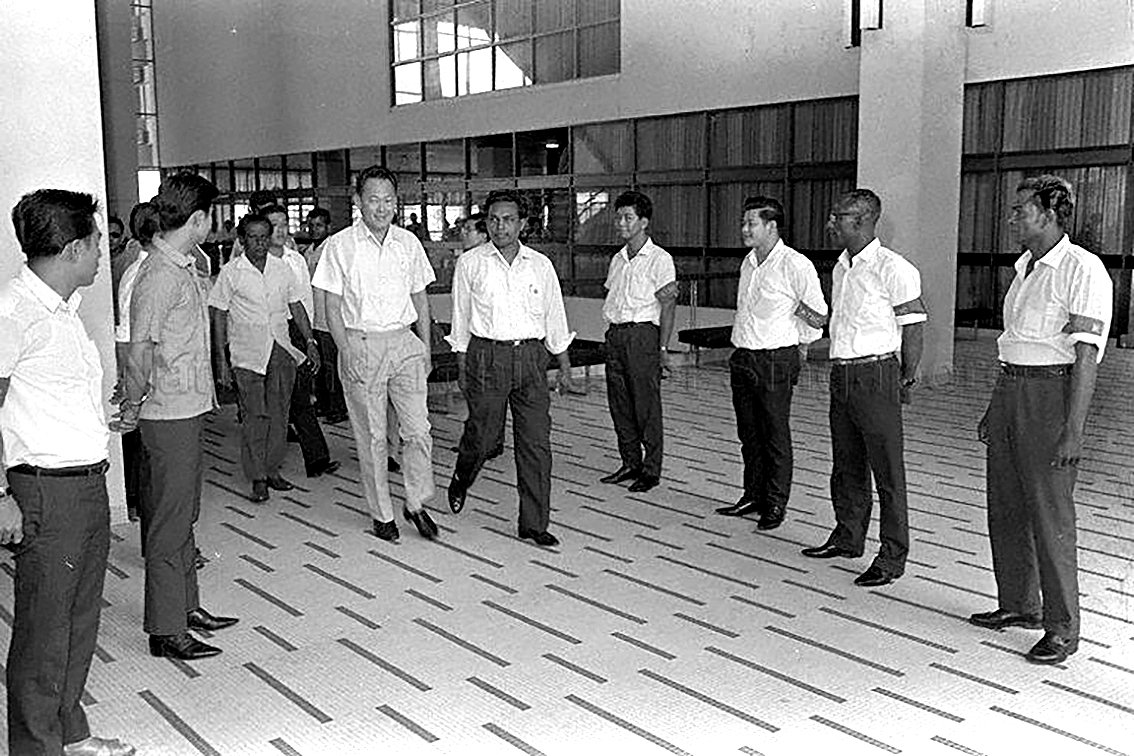

When the SCHTUH was completed, Singapore’s founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew expressed great admiration for it. He said it demonstrated “a finesse and a delicacy and a pride of performance” by Singapore labourers that stood for the rugged, disciplined society that he wanted to forge out of our young nation.

“As I walked into this chamber, I swelled with pride, pride at the capacity of my fellow citizens… I have been to many conference halls, I have been to many an imposing building. But from the corner of your eye, never mind the size of this structure, as you walk across the floor, see whether the people have the verve and the capacity and a pride in performance,” he said.

The labourers and architects of this building certainly did. Beyond its imposing modernity, what stood out for Mr Lee was its quality of finish. “But out of the corner of your eyes, you watch the quality of the finish, whether the doors click when you close or whether you have got to give it an extra push. It is a matter of quality of workmanship,” he noted.

The ultimate test forLee was in the toilet. He was duly impressed by the care and detail the labourers put into customizing the installation of wall tiles, pipes and washbasin. “The last tile is half an inch from the basin. If it were any other place, they would have said, ‘Say, just put a bit of paint and forget it!’ But they chipped off a half-inch of tile all along, seven pieces, and then completed a square. And I said, ‘Boy, this place has got it!’”

A time of shaping the future

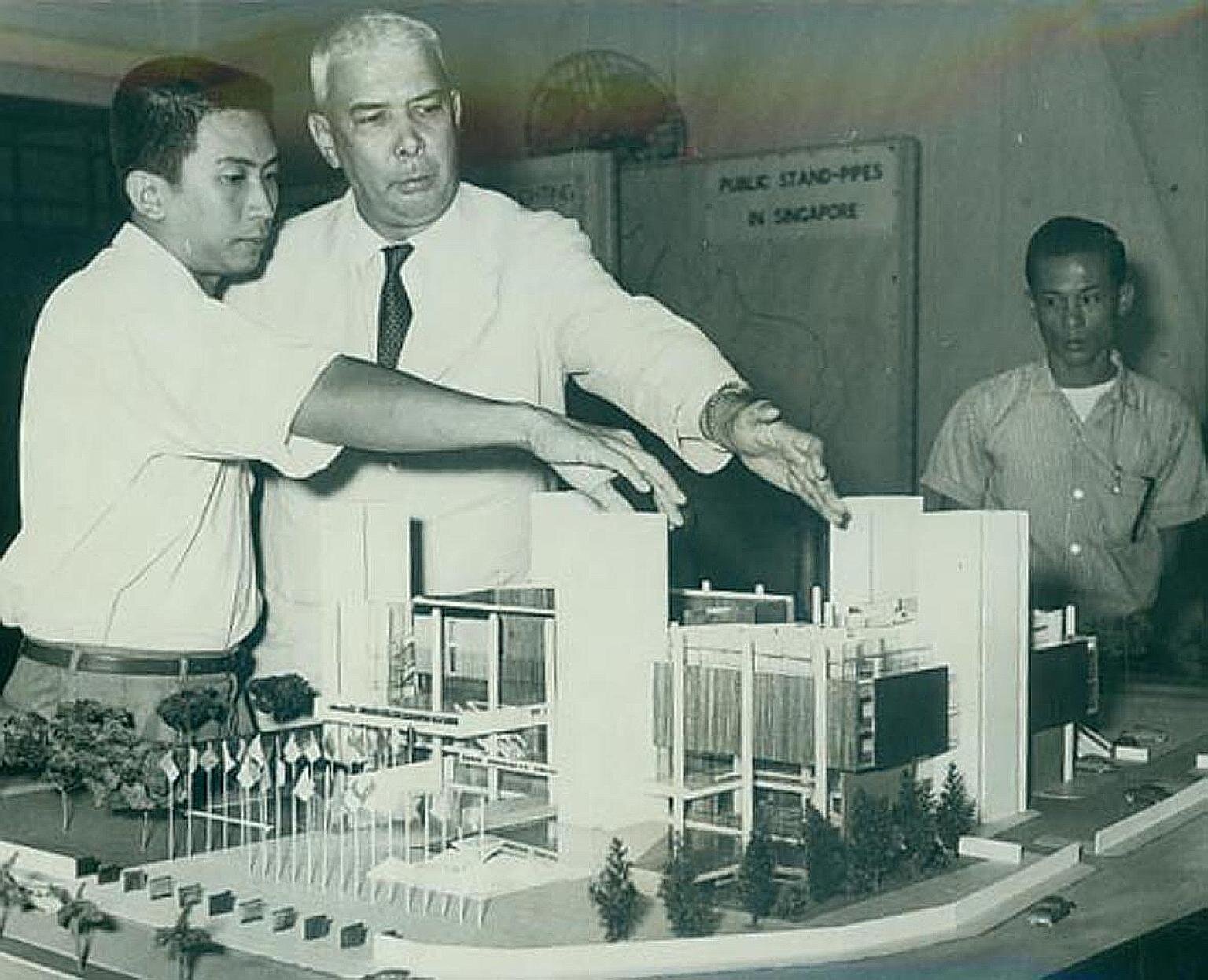

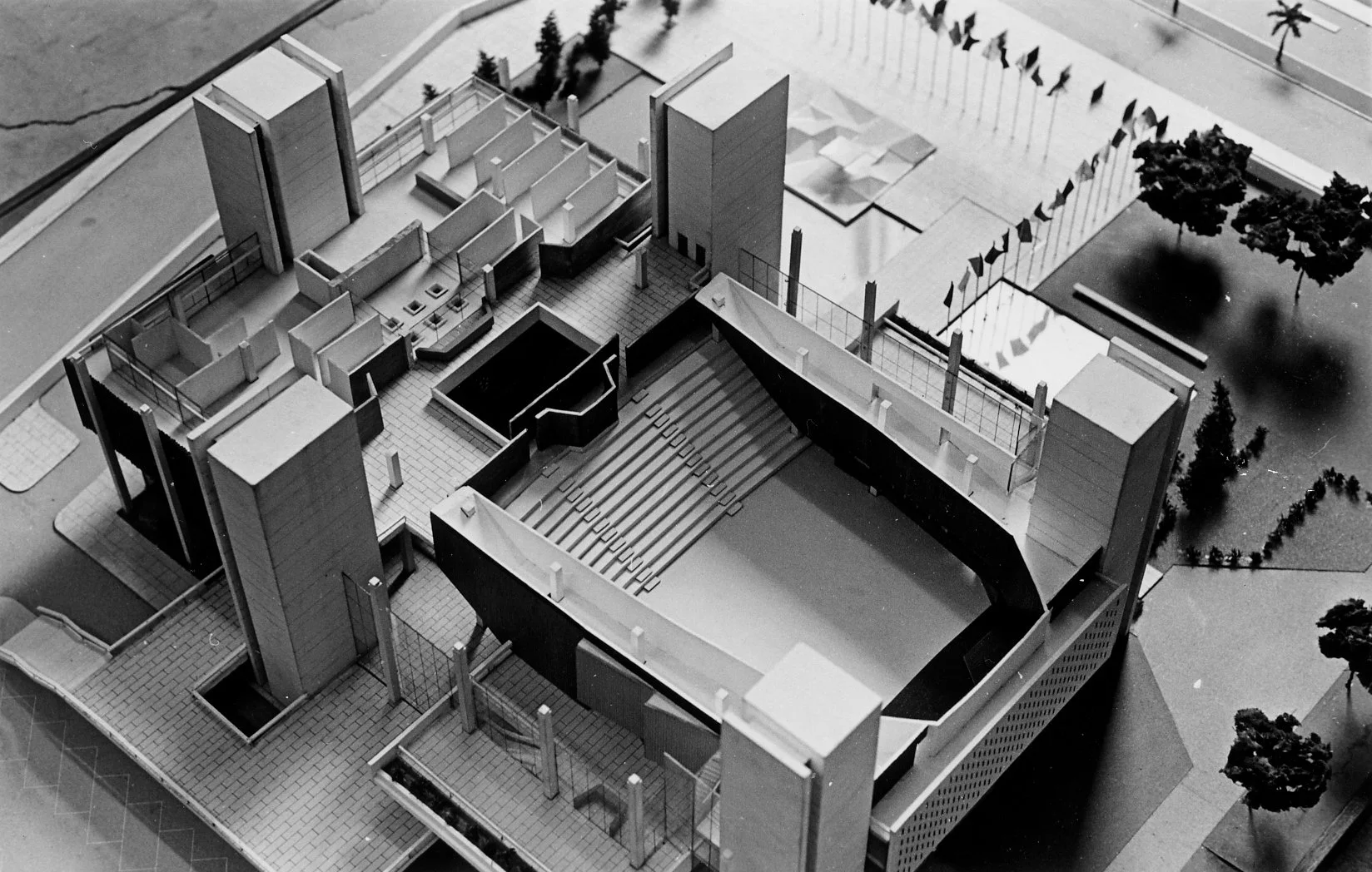

What is also impressive about the SCHTUH was the fact that it was designed by a team of freshly minted architects who were then only in their late 20s and early 30s. Lim Chong Keat, Chen Voon Fee, and William Lim had co-founded the Malayan Architects Co-Partnership (MAC) in 1961 after returning from the United Kingdom, where they studied architecture. A year later, they won a high-profile open design competition for the building. It was a significant achievement for such a young practice to secure a major commission for a prominent civic and cultural monument.

Veteran architect Tay Kheng Soon, who was then an architecture student at Singapore Polytechnic and had interned at the young firm, recounted:

“The MAC submission stood out by the sheer virtuosity of the design. The drawings were printed on textured sepia ammonia print… different from all the other entries, which were printed with the usual blue/black line ammonia paper. The quality of the line work was also different. The use of shadow and shade brought out the depth and layering of the planes and masses.”

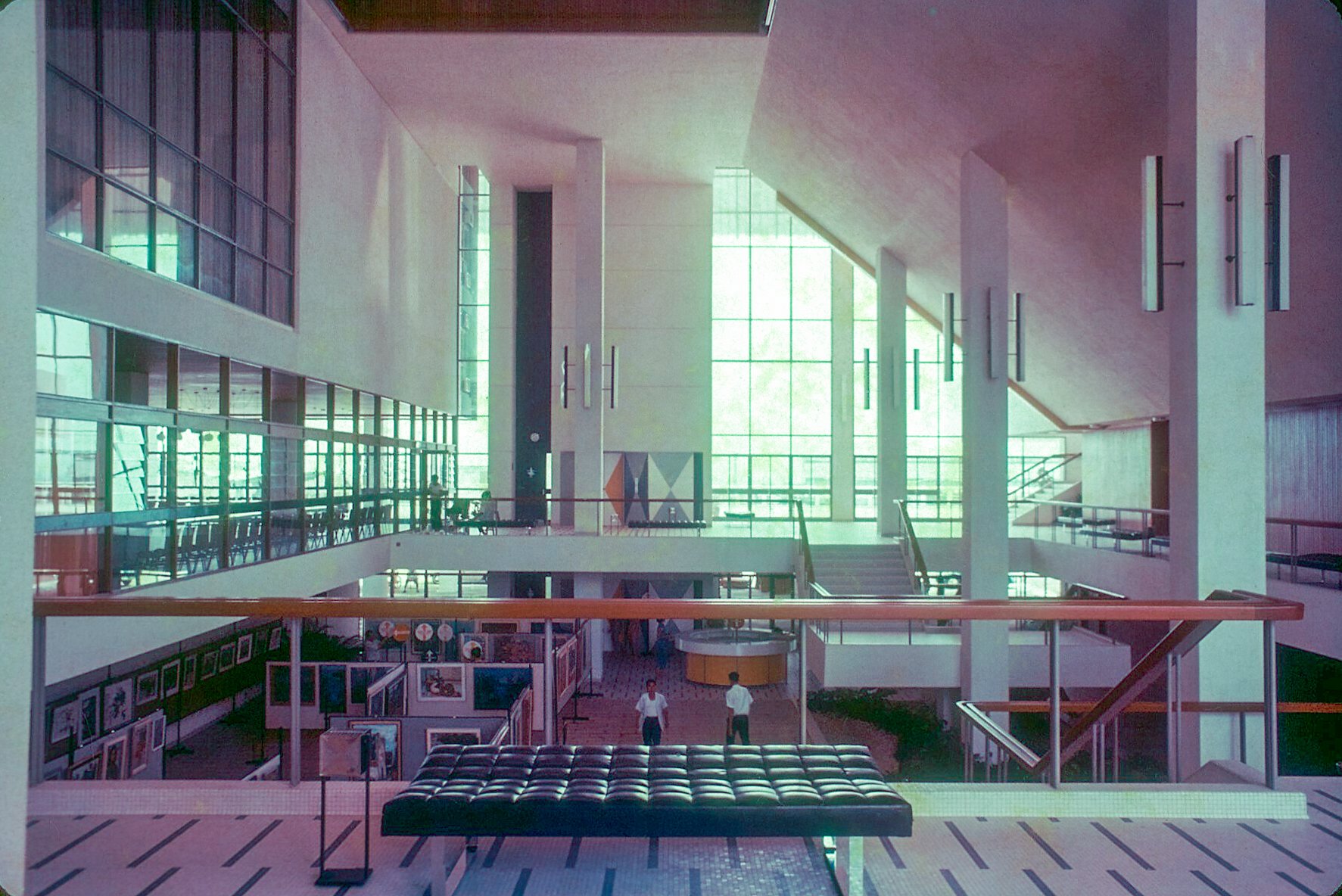

“The scheme was a fully integrated design in plan, section and elevation, … three-dimensionally … by a plastic connective space. This was thoroughly new, even revolutionary. … The need for spill-out spaces from the hall during intervals led to pulling out beyond the nominal façade line several tray-like platforms that were made to seemingly float against the masses behind. The main concourse on the first level was conceived as a giant social space for exhibitions and from which visitors may fluidly find their way to various lifts, lobbies and other spaces beyond.”

The design reflected the experience of the Modern Movement firsthand by the co-founders of MAC who been mentored by some of its key figures. Lim Chong Keat also brought Bauhaus teaching methods directly to the architecture school at Singapore Polytechnic, which he helped establish. The modernist worldview of these young graduates, who hailed from Penang, Ipoh, and Singapore, were also shaped by a new nationalist consciousness to contribute to the creation of a new society.

In a 2001 television interview, Lim Chong Keat recalled that the building emerged during “a time of ferment… (a) time of shaping the future.” He and his team poured their heart and soul into the design, “from the furniture to the mosaics to the paintings,” including the landscaping and the trees. He added: “You spend sleepless nights over a project; you eat, live, and breathe it.”

A modern aesthetic rooted in regional traditions

The original Singapore Conference Hall and Trade Union House was much admired for its clarity of structure, fluidity of composition, and spatial ambiguity between inside and outside. In 2001, Tay even hailed it as “an innovative attempt at evolving a modern tropical design language that has not been matched since.”

Less known, however, is the traditional woven mats made of mengkuang (screw pine leaves) that inspired the abstract patterns of glass mosaics that covered parts of the auditorium walls. This came from Lim Chong Keat’s fascination with vernacular Malay architecture. Besides taking his students to study Malay houses and curating exhibitions of such regional vernacular architecture, he also inherited a collection of beautiful measured drawings of mengkuang mats of vernacular houses from the late Carl Alexander Gibson-Hill (1911-1963). These drawings were probably prepared as illustrations for articles in the Journal of the Malayan Branch of Royal Asiatic Society (JMBRAS) that Gibson-Hill edited.

The mengkuang woven mat was also featured on the cover of the first few issues of PETA, the Journal of the Federation of Malaya Society of Architects. They were published between 1955 and 1956, at the height of the debate on Malayanisation and Malayan Architecture in the late-colonial era. The incorporation of a woven mengkuang mat pattern in an exemplary modernist building could be read as an attempt by the architects to create a modern aesthetic based on regional traditions for a newly-independent multi-ethnic nation.

Early witness to Singapore’s international links

In its early years, the SCHTUH hosted many of Singapore’s early exchanges with the rest of the world. Shortly after its opening in October 1965, the National Trades Union Congress’ (NTUC) Second Annual Delegates Conference was held in the building and the event was attended by trade union delegates from 11 African countries. Their visit came on the back of Lee’s tour of 17 countries over 35 days a year earlier in 1964, which paved the way for relations with Africa’s newly-independent nations as part of the Non-Aligned Movement.

These links with the Global South continued to grow. In 1967, the building hosted the Afro-Asian Housing Congress that showcased Singapore’s nascent public housing programme to the world. During the event, then Minister for Law and National Development E. W. Barker said: “Afro-Asian countries realise that the problems we face must in the final analysis be solved by our own efforts and using our own ingenuity to devise the answer to these problems”. It is an apt comment that equally applies to the architecture of the SCHTUH.

Many world leaders set foot through the doors of SCHTUH too. One of them was the first “Iron Lady” Indira Gandhi, Prime Minister of India who made a state visit to Singapore in May 1968. She was hosted by Lee to a state banquet in her honour at the SCHTUH. This was the first visit to Singapore by an Indian Head-of-State. At that event, Lee honoured her as “the head of a government which represents a people who have given us a part of ourselves and more than part of our inspiration.”

SCHTUH was also the venue for the first globally-significant summit hosted in Singapore. The 1971 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting was the first time that this political gathering was held outside of the UK. The 31 Heads-of-State and Senior Ministers who attended included legends like Julius Nyere (Tanzania), Sirimavo Bandaranaike (Sri Lanka), and Pierre Trudeau (Canada, father of Justin Trudeau). The event concluded with the Singapore Declaration of Commonwealth Principles, which proclaimed that “expanded human understanding and understanding among nations will help the elimination of discrimination based on differences of race, colour or creed.”

Restoring a national monument for SG60

In the early 2000s, the SCHTUH underwent extensive renovations. This unfortunately compromised its original design and many of its most distinctive architectural features—hallmarks of Singapore’s modernist heritage—were obscured, modified, or removed entirely. Even though the building was gazetted as a national monument in 2010 in recognition of its significance in Singapore history, these insensitive alterations remained.

Docomomo Singapore believes it's time to reverse the damage and restore the monument’s integrity and dignity. Here's how:

Reinstate key interior spaces and relationships, including the former TUH library’s double-volume space and the transparent glazing between SCH and TUH, to revive their original spatial continuity and historic connection.

Recover the original architectural form and massing by removing or modifying intrusive later additions—such as the 'box' frame over the original balconies—and reopening the civic forecourt to enhance the intended openness and public character of the monument.

Restore the modernist material palette by removing inappropriate finishes like the yellow paint concealing the original white Shanghai plaster.

Reinstate the timber strip cladding in the SCH auditorium and patterned mosaic flooring to bring back the material honesty and texture of the original design.

As Singapore approaches the 60th anniversary of its independence—and of the completion of SCHTUH itself—we urge state agencies, authorities, landlord, tenants and the public to support the careful and respectful conservation of this landmark. It is time to rectify past mistakes and ensure that SCHTUH can once again serve as a dignified monument to our nation’s journey.

Sources:

Souvenir Brochure for the Opening of the Singapore Conference Hall & Trade Union House on 15th October, 1965 (Singapore: Singapore Government, 1965).

Speeches by Lee Kuan Yew at the Opening Ceremony of the Singapore Conference Hall & Trade Union House (15 Oct 1965) and 15th Anniversary Celebration of Singapore Printing Employees Union (17 Oct 1965)

Jiat-Hwee Chang, “Race and Tropical Architecture: The Climate of Decolonization and Malayanization,” in Race and Modern Architecture, ed. Irene Cheng, Charles L. Davis, and Mabel O. Wilson (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020), 241–58.

Dinesh Naidu, “Lim Chong Keat”; in Leo Suryadinata, ed., Southeast Asian Personalities of Chinese Descent: A Biographical Dictionary, Volume I (Singapore: ISEAS Publishing, 2012) republished in Docomomo Singapore website <https://www.docomomo.sg/people-and-organisations/lim-chong-keat>

Tay, Kheng Soon, “Trade Union House & Singapore Conference Hall at Shenton Way” in Singapore Architect Issue 202, Singapore: Singapore Institute of Architects, 2001.

Building Dreams documentary episode 1, directed by Tan Pin Pin, Singapore: Xtreme Media, 2001 <https://vimeo.com/128958960>

This article was adapted from a series of DocomomoSG social media posts between May and June 2025 created by Chang Jiat Hwee and Ronald Lim.